A sprawling Maya city with palaces and pyramids was discovered in a dense Mexican jungle by a doctoral student who unknowingly drove past the site years ago on a visit to Mexico.

Tulane University archeology doctoral student Luke Auld-Thomas was in Mexico about a decade ago traveling between the town of Xpujil, an archaeology site, and coastal cities, when he drove past the unexplored settlements burrowed deep in the landscape.

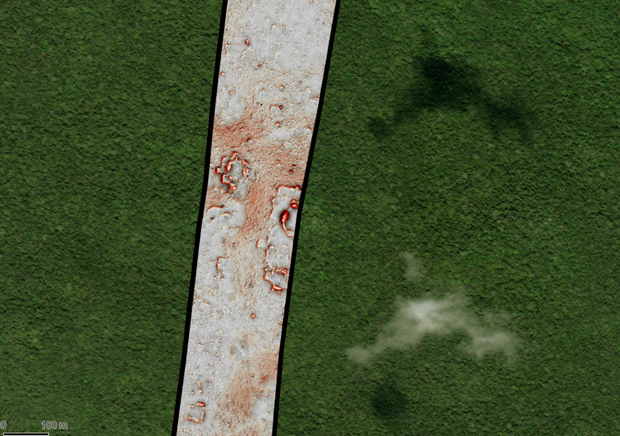

But combing through those dense jungles needed the assistance of Lidar, a remote sensing technology that uses lasers to measure the distances of objects on the Earth’s surface.

And this can be very costly. Funders are often reluctant to invest in Lidar surveys in areas where no visible evidence of Mayan settlements exist, Auld-Thomas said.

But, several years later Auld-Thomas had an idea. He would use pre-existing surveys to find out if Maya civilizations could be located in these areas.

“Scientists in ecology, forestry and civil engineering have been using lidar surveys to study some of these areas for totally separate purposes,” says Auld-Thomas in a news release Tuesday. “So what if a lidar survey of this area already existed?”

Tulane University

In 2018, Auld-Thomas, an instructor at Northern Arizona University, located data collected in 2013 in a project spearheaded by Mexico’s Nature Conservancy to monitor carbon in Mexico’s forests. The previous team’s aim was to map above-ground carbon in forests.

The publicly available dataset allowed Auld-Thomas’ research team to identify the site as a terrain meriting further archeological investigation.

Over a period of five years, Auld-Thomas and his team analyzed everything remotely, using technology and analysis. And when Auld-Thomas analyzed that data, he stumbled onto a huge surprise — evidence of more than 6,600 Maya structures, including a previously unknown large city complete with iconic stone pyramids.

The team hadn’t anticipated discovering an ancient city that would put to rest persisting doubts among researchers that the Maya lowlands region was potentially not as populous and urbanized as researchers believed. It also validates previous research and puts an enduring question to rest.

“It does not reveal a different perspective on Maya urbanism and landscapes, it actually shows us that the perspective we already had is pretty accurate,” he said adding the “number of buildings present in the entire data set is high enough to speak of genuinely high regional scale population entities.”

Researchers published their findings on Tuesday in the journal Antiquity, describing the vast structures and buildings comprising the ancient city named “Valeriana” after a nearby freshwater lagoon. The team collaborated with Mexico’s Cultural Heritage Institute, local archaeologists, and the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping at the University of Houston that enabled them to conduct the research remotely.

“This density is comparable to that of Mayan sites such as Calakmul, Oxpemul and Becán,” said Adriana Velázquez Morlet, director of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History Campeche Center, and one of the research’s co-authors, in a statement.

He added that their institute is working with local populations to ensure the new site’s conservation.

Auld-Thomas said that archaeologists who know the region well were able to improve the team’s analysis and provide “a really deep perspective on this region.”

Tulane University

“The nature of the ruins, the archeological buildings that were there — they were big and they were instantly recognizable as the kind of things that mark political capital of the Maya Classic period,” Auld-Thomas told CBS News.

The height of the Mayan empire was the Classic period, which spanned from approximately 250 A.D to at least 900 A.D., when they made breakthroughs in astronomy, hieroglyphic writings and the calendar system.

Arguably the most advanced civilization in the Americas, the empire once occupied what is now southern Mexico and northern Central America, including the countries of Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. Roughly 7 to 11 million people lived in the Maya civilization during this time, according to a 2018 study in the journal Science.

Auld-Thomas said his team analyzed 50 square miles, and found that the city of Valeriana — which was built before 150 AD — contains thousands of structures including palaces, temple pyramids, public plazas, a ballcourt, a reservoir and family homes. The technology allowed researchers to view archaeological settlements even in dense forest conditions in the southeastern Mexican state of Campeche.

Archaeologists in 2018 uncovered a massive network of Maya ruins hidden for centuries in the jungles of Guatemala. In 2022, human burial grounds and bullets from Spanish guns were discovered at a Maya city site in the country.

Auld-Thomas said the reason large parts of the Maya world are archaeologically unknown is because the region is so vast, leaving large swathes of it unexplored by researchers who then document its existence. Auld-Thomas said locals might have known about the structures, but the government and the larger scientific community did not.

“That really puts an exclamation point behind the statement that, no, we have not found everything, and yes, there’s a lot more to be discovered,” Auld-Thomas said in a Tulane University press release.

He also said the research underscored the value of open data in science, and that data gathered by someone in one discipline might prove useful for someone in a completely different research field.

“What I hope is that this encourages not only open data generally, but also collaboration between archeologists and environmental scientists going forward.”