In 2005, Rushia Brown, a former WNBA forward and front office executive, attended a fundraising event in Texas with several other retired players. The group, including Hall of Famers Teresa Weatherspoon, Cynthia Cooper and Lynette Woodard, gathered to play in a celebrity game against a group of local girls with professional aspirations.

The night before, when the former WNBA players arrived, Brown and the other players noticed one of their former colleagues looked “unkept” during their conversations, only to find out minutes later that she was homeless.

“I went to the WNBA, I went to the NBRPA, and the board, at that time, did not think that they should serve the women,” Brown said.

After the board of directors refused to integrate retired WNBA players, Charles Smith, then president and CEO of the NBRPA, helped Brown form her own organization, which eventually became the Women’s Professional Basketball Alumnae. Fresh off of playing, Brown had not yet transitioned into a second career. She also received no pension and health insurance from the WNBA, something all former players are individually responsible for.

But because of her passion to assist professional women’s basketball in retirement, Brown funded the majority of the organization on her own.

“It was something that needed to be done because I knew the importance of this organization, but (the NBRPA) wasn’t available to us yet,” she said.

The Women’s Professional Basketball Alumnae provided support for retired women, similar to what the NBRPA does for men. When Scott Rochelle, the president and CEO until August 2024, joined the NBRPA as vice president of membership in 2013, the women were just being integrated into the organization. One of his main responsibilities was figuring out how to best incorporate these former players.

“I’ll say there was at least a year of getting feedback, engaging with the community, to figure out what exactly their needs were, because we couldn’t just take our NBRPA offerings and just apply it,” Rochelle said. “That wasn’t going to work, and we weren’t going to be able to have conversations with these women who had left the league and essentially been left alone for years and assume they were just going to jump in with open arms.”

Rochelle knew Brown was the key factor in “marrying” the Women’s Professional Basketball Alumnae and the NBRPA.

“One of my first duties was to find Rushia and sit down with her,” Rochelle said. “To her credit, she held my feet to the fire. She really asked the right questions. I went to Atlanta to meet with her. We sat down, we talked, and from there, I just had to do what I said I was going to do and be very intentional about growing.”

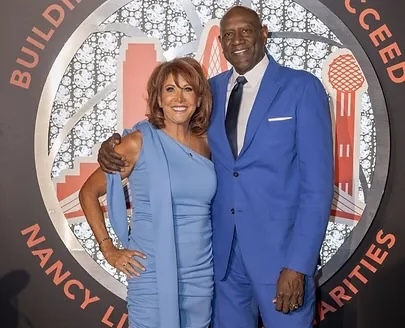

Along with Brown, Hall of Famers Sheryl Swoopes and Nancy Lieberman have been trailblazing advocates for expanding the NBRPA to include former WNBA players.

Lieberman is familiar with the term “trailblazing.” She was the first woman to play in a men’s professional league when joining the United States Basketball League’s Springfield Fame in 1986. She also appeared in a WNBA game at 50 years old. When she joined the NBRPA, she became the first woman to ever sit on its board, bringing a determined and businesslike mindset to the organization.

“We’re in the business of sports,” Lieberman said. “This is not the girls club. We have to take care of the past; we have to take care of the players right now; we have to look to the future.”

In February, she was named treasurer of the organization, the same time that Brown was elected to her role as director. Now, the two are striving for a defiant change that would alter the future of retired WNBA players. So is Spencer Haywood, a basketball Hall of Famer who sued the NBA for the right to play in the league less than four years after high school. Haywood was reelected as an NBRPA director, advocating on behalf of not only retired women, but also his late wife Linda.

“She was quite friendly with the (WNBA) ladies,” Haywood said. “Before she moved on, she said, ‘Whatever you do, you do this for the women because you are a father of four daughters.’”

Linda Haywood was an executive at Blue Cross Blue Shield, and very close friends with Brown. The fight that she wanted Haywood to embark on with Brown and Lieberman was to ensure that retired women receive health insurance and pensions after their basketball careers end. Currently, there are no such opportunities in the WNBA’s Collective Bargaining Agreement.

The need for retirement benefits for the former players, especially health insurance, is clear. Since October 2022, former WNBA players Tasha Butts, Nikki McCray-Penson and Tiffany Jackson have died from breast cancer while former Seattle Storm center Simone Edwards died from ovarian cancer.

“The (WNBA), I feel like, has to make sure that they’re investing in the women who laid the foundation,” Brown said.

“I think so many times we go without having the conversations about the number of women that we’ve lost to cancer here in the last two years, two of which I know for sure did not have insurance. That’s absolutely unacceptable, to have invested seven, 10, 12 years into a job, in a league, and you not have insurance and you not have a pension.”

The WNBA did not respond to a request for comment.

For the retired women to receive this support, the WNBA and Women’s National Basketball Players Association must reach an agreement in the league’s next Collective Bargaining Agreement. Conveniently, the timing aligns well: on October 21, 2024, WNBA players opted out of their current Collective Bargaining Agreement, which will expire on October 31, 2025. This gives both parties a year to negotiate the next agreement.

Brown said that the NBRPA has begun discussions with the players association and Executive Director Terri Jackson related to health insurance and pensions, but those conversations “are not at the forefront.” The Women’s National Basketball Players Association and Jackson declined to comment for this story.

“The thing that we have to do is make sure that we increase the conversation and talk to them about how important it is to push this because this is perfect timing,” Brown said.

Rochelle also believes it is the right time to implement these benefits, mainly because of the $2.2 billion that the WNBA will receive as part of the NBA’s 11-year deal with Amazon, Disney and NBC for broadcasting rights.

Related NewsArticle continues below

“We calculated about $4 million would be needed annually to cover the women in the same way in which the men are covered,” Rochelle said.

The WNBA will receive $200 million annually from the television contract, meaning just 2% of that annual contract could provide retired women with health insurance and pensions equivalent to that of retired NBA players.

“The time is right for us to be in position to not only advocate, but really demand that there be a retired player conversation and a seat at the table during the next Collective Bargaining Agreement,” Rochelle said.

Pensions have been a part of the NBA’s Collective Bargaining Agreement since 1965, but it was just eight years ago, in 2016, when the National Basketball Retired Players Association proposed adding a health insurance plan for retirees. Players including LeBron James, Chris Paul and Andre Iguodala drove this effort and made it a “very high priority,” according to Rochelle.

After the 2024 WNBA All-Star Game, perhaps the most successful in the league’s history with 3.44 million people watching the game on ABC, ESPN’s Alexa Philippou asked current players “what they consider the league’s most pressing issues moving forward.” Nneka Ogwumike, Breanna Stewart and Kelsey Plum, all three of whom are on the executive committee for the National Women’s Basketball Players Association, advocated for taking care of the women that laid the foundation.

“You look at the players that started and paved the way for this league, and there’s nothing [for them],” Stewart told ESPN. “They don’t get anything from where we are now. So that could be something that I think is really important.”

When Brown created the Women’s Professional Basketball Alumnae, she envisioned an organization that not only supported retired women’s basketball players, but also informed the current players about what’s next in their lives. After bringing her values and initiatives to the NBRPA, she craves the opportunity to continue informing and advocating for a group of retirees that will only grow as players reach the end of their athletic careers.

“I relish that opportunity because I know that I can impact change and just give them something else to think about,” Brown said. “Everybody that plays this game is going to be retired at some point. Whether you leave the game or the game leaves you, you’ve got to think about what life looks like beyond basketball.”